It’s that time of year once again. Daylight savings has lengthened our evenings and the sun can feel soft on your face and encouraging for the little sprouts emerging from the garden beds. Then the next day, the clouds and the wind roll in and you’re reaching again for your hat and gloves. But at least there’s hope that spring (the real deal, not just the date on the calendar) is on its way, something that’s probably not yet true for those living in Maine or Minnesota.

When the daffodils start to make their appearances in sunny spots ( for example, the long expanse on the west side of Rock Creek Parkway between P Street and the Whitehurst Freeway), I always think of my grandfather, Abraham Bernard Schwartz who was born on March 14, 1891 in Macon, Georgia. Beb, as he was known from childhood, had a quite different back story from his wife whom I wrote about previously.

Beb was the first in his family to be born in the U.S., preceded by an older sister, Annie, and brother, Louis, who travelled with their parents from their birthplace in Volkovysk, in the region then known as the Pale of Settlement within the Russian empire, now part of Belarus. Family lore says that they ended up in Macon to escape a yellow fever epidemic raging in Savannah where they landed but there’s no documentation to confirm this. An alternative story suggests that they entered the U.S. through the port of Baltimore but I can’t find any ship log confirming the time and place of their entry. (Henry Louis Gates, Jr. — where are you when I need you?!)

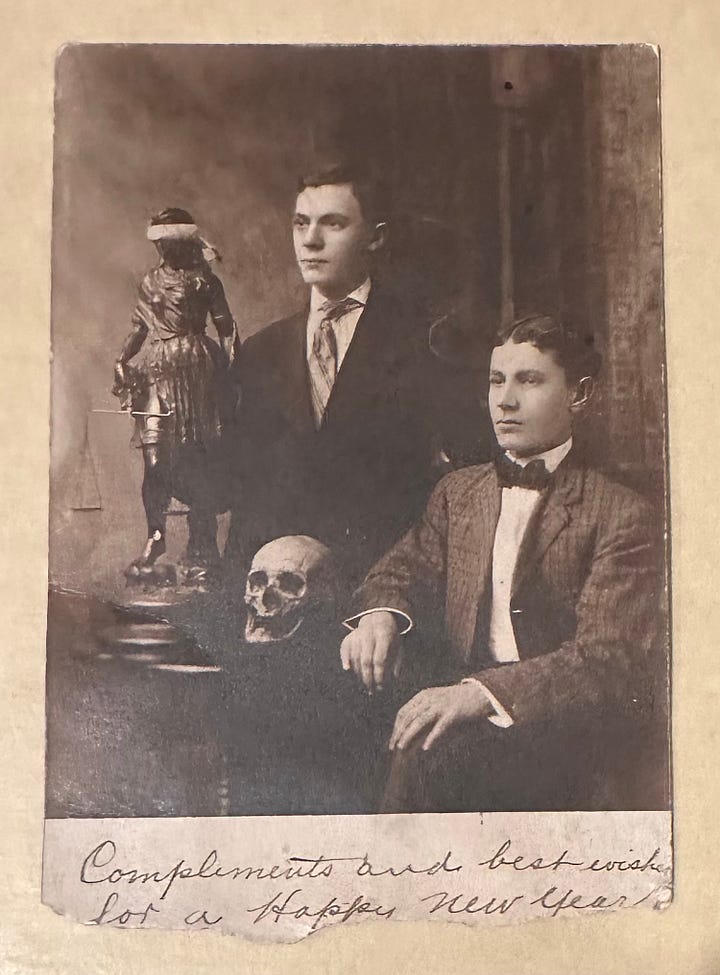

In any case, by 1898, they had made their way to Atlanta, their family now grown to eight with the addition of yet another son and two little sisters. My grandfather eventually matriculated at the Atlanta College of Physicians and Surgeons which later became part of Emory University, coincidentally where my father many years later joined the faculty. Pennies were scarce in the household as his father apparently spent more time studying and arguing about the Talmud than earning a living, so Beb worked as a custodian to cover his school fees. He rode on one of the last horse drawn ambulances down Butler Street (since renamed as Jesse Hill Jr Drive), where Grady Memorial Hospital still stands, and asked for special consideration so he could attend synagogue rather than medical school classes on Saturdays. After graduation, he continued his training in Boston and Chicago, and finally set up a private practice of pediatrics in Milwaukee in 1916. The idea of a specialty focusing on children was so new at the time that my grandmother initially thought he was a podiatrist.

Pediatrics was a perfect match for Beb as he had a gentle soul, a kind manner, and wonderful sense of humor. His practice consisted of early morning phone calls at the breakfast table, followed by rounds at the hospital, and house calls until lunch time. After taking a restorative nap at home, he would head to the office to see more patients followed by even more phone calls. He cared for children living in crowded conditions in South Milwaukee (perhaps not unlike the home he grew up in) and those who lived on big estates in River Hills, well north of downtown. My dad recalled the novelty of going on house calls in a car with a search light (to see house numbers at night) and a memorable weekend house call to an enormous property in tony Oconomowoc, “where there were armed guards due to the threat of a kidnapping and Dad was questioned by one of the guards before we could drive up to the big house.”

Beb shared my grandmother Irma’s love of books and learning and his reading diet included topics in pediatrics, allergy, and child development, religious texts in Hebrew, and the comics page. In addition to being a role model for my dad and his brother (who both became physicians), he also supported his siblings and helped nieces and nephews pursue their dreams of higher education. He always wore a bow tie, a practical tactic for a pediatrician who didn’t want babies yanking on his tie; in fact, I’m not sure I ever saw him without one. He made scrapbooks and wrote silly poems, some of which were published as letters to the editor of various medical journals.

Sadly in his 90s, Alzheimer’s disease destroyed Beb’s mind, leaving a shell of the man he once was, prone to outbursts of anger and sometimes cursing the nursing home aides who cared for him. My dad wouldn’t let me and my siblings visit him during those years, hoping that we would remember our grandfather as the loving and learned person he had always been. I am grateful for this small kindness. While I remember the last time I saw him, his frail frame (still in suit and bow tie) hunched over a walker, perhaps two years before his death in 1986, the more enduring memories are ones that bring me a lot of joy plus a few tears.

What a handsome man who clearly was very special. You were a very cute toddler.

Beautiful