One hundred twenty eight years ago today, my paternal grandmother, Irma Friedlaender, was born in Columbus, Georgia. I’m not going to say that she would be 128 if she were alive because a) that’s just plain silly and b) she lived to be 106 which is quite enough years for anyone.

Grandmother (and that’s what she insisted on being called — no “grandma” or “granny” or certainly not “mamaw” for her) was not many of the things that grandmothers are supposed to be. She wasn’t nurturing or cuddly. She wasn’t a good cook and made strange choices in the kitchen such as mixing multiple flavors of ice cream together or combining several types of cereal in one box. She was critical of bad manners, sloppy thinking, ostentation, and all manner of other things, including how the Episcopal priest at her retirement home interpreted the scripture. But I, along with my brother and sister and our two cousins, loved her fiercely, admiring her intelligence, quick wit and musical laugh, all of us beneficiaries to frequent chatty letters, colorful stories about her childhood, and attentive interest in all our hobbies and pursuits. As we became adults, a visit to her required advance preparation to respond to her queries, whether they be about politics, philosophy, or books. She read through the collection of the Great Books numerous times and stayed up to date on world events; although she wouldn’t have a television in the living room, each night, she rolled the set on a little cart out of the closet so she could watch McNeil-Lehrer.

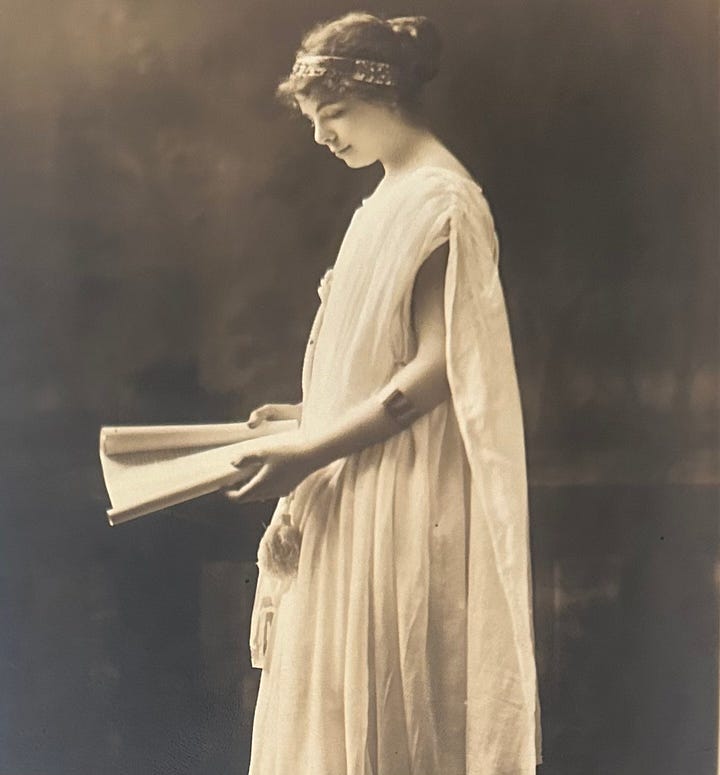

As the photo below so clearly demonstrates, she was born into privilege. Her father came from Germany to the U.S. as a young man to work for his uncle and eventually opened his own establishment, a factory that made jute bagging for cotton. They lived in a big house with servants, and she went off to college at Wellesley and her brother to Princeton and then Harvard and the University of Chicago. She had expensive tastes, wearing Ferragamo heels well into her 90s, insisting that they were the only shoes that fit her narrow feet. But she was also thrifty, using pencils until they were so small you could barely hold them and keeping a box for “pieces of string too small to save.” In a letter to my parents after a visit when they brought flowers, she admonished my dad for tying the ribbon on the bouquet too tightly so “that I can’t iron out the creases so the ribbon may be re-used.”

She met my grandfather Beb at a wedding in Alabama, where she was a friend of the bride and he a former classmate of the groom. Despite the fact that he was a doctor and Jewish, my great grandparents considered him unsuitable in every way. He was the son of recent immigrants from what is now Belarus. They had no money and his parents barely spoke English. Although born and raised in Georgia, he had established his medical practice in faraway Milwaukee. But my grandmother, being stubborn and probably considered an old maid at the age of 27, stood her ground. They were married in what was described in the society column of the Columbus Ledger as “one of the most elaborate and beautiful weddings in the history of Columbus.” They headed north afterwards, stopping for a honeymoon at The Greenbrier in White Sulfur Springs, Virginia, my grandmother with a purse of money foisted on her by her father in case she needed funds to return home.

I guess the money used for lilies, candles, satin gown, and an orchestra was well spent. Irma and Beb adored each other, leaving behind after more than 60 years of marriage stacks of handmade birthday cards and Valentine poems that they exchanged, many addressed to “my sweet puddin’.”

Irma remained sharp as tack, even as she passed her 100th birthday. There were a few gaps: she couldn’t remember the name of my sister’s husband (which for the record was David, just like my brother and husband). And she couldn’t quite grasp what a personal computer could do. But when I think about the changes she lived through — the appearance of Halley’s Comet in both 1910 and 1986, the switch from horses to automobiles, the ease of air travel (compared to the days of train travel that it took for her to get to and from college) to name a few — surely she deserved some grace.

Life faded for my grandmother during her last few years. Although she remained remarkably healthy, even recovering after a broken hip at 98, nothing much held her interest. She’d outlived her husband, two sons, and most of her friends. Her eyesight was such that reading was no longer possible. It made me realize that a life lived too long, even if free from illness, is its own kind of suffering. (I wrote about the aftermath of all this on my previous blog here.)

But today, I’m thinking of happier times. I have the pictures, letters, and little notes in her handwriting explaining the provenance of different items she passed down. I’m remembering her love of Planter’s peanut candy, her skill at flower arranging, and the orange juice she’d push on me so I wouldn’t get scurvy, served in a crystal old-fashioned glass on a china saucer. My home is filled with furnishings and artwork she picked out for her own spaces, and the shelves by my desk are populated by tiny wooden and china figurines that were once residents of pigeon holes above her own desk — all lovely memories of a most remarkable woman. Happy birthday Grandmother.

Thank you Anne, for that lovely remembrance of Grandmother. I remember visiting her in Milwaukee in the late 80's, and finding a small collection of twist-ties in the front of one of her kitchen drawers, her thrift a trait my father inherited as well.

What a great story and the family resemblance is striking!